Smartphones are dead Part II: Evolve or die, Microsoft's ultra-mobile PC strategy

Consumers and app developers are demanding increasingly sophisticated personal computing from the smartphones that we carry with us daily.

This demand has led to an evolution of smartphone hardware and consumer usage that positions these devices more as mini-tablet computers than phones. In fact, we established in part one of this series that current smartphones are indeed mini-tablet PCs that are an "evolutionary" step between phones and the next phase of personal computing. Ultra-mobile personal computers (as I am calling them) will be pocketable all-in-one devices that take advantage of a universal platform, context sensitive hardware and software, universal apps and the cloud to facilitate the mobility of a user's digital experiences.

I contend that our current "smartphones," which have replaced small tablets, which replaced desktop PCs for an increasing number of personal computing tasks, will continue their trek toward the all-in-one ultra-mobile device capable of managing an increasingly complex array of personal computing tasks previously reserved to the traditional desktop environment.

This smartphone evolution in its current "mini-tablet" state is, of course, a device-agnostic transition. iPhones, Android devices, and Windows phones have all reached dimensions, functionality and usage that qualify them as mini-tablets. Indeed, each of these platforms is represented in the market by devices that occupy this transitory phase preceding the advent of the true ultra-mobile PC.

However, this current smartphone landscape, which is dominated by the iPhone and a host of Android devices, has virtually plateaued. As a result of a "phone-focused" paradigm, these two dominant platforms impose inherent barriers to evolving into personal computing's next phase. I believe, however, that Microsoft may possess the missing link.

Evolutionary dead end

Microsoft's CEO Satya Nadella had the following to say regarding Redmond's future in the mobile landscape and mobile computing's evolution:

If anything, one big mistake we made in our past was to think of the PC as the hub for everything for all time to come...today…the high volume device is the six-inch phone...But to think that that's what the future is for all time to come would be to make the same mistake we made in the past…Therefore, we have to be on the hunt for what's the next bend in the curve…We're doing that with our innovation in Windows…features like Continuum.Even the phone, I just don't want to build another phone, a copycat phone operating system, even…when I think about our Windows Phone, I want it to stand for something like Continuum. When I say, wow, that's an interesting approach where you can have a phone and that same phone, because of our universal platform with Continuum, can, in fact, be a desktop. That is not something any other phone operating system or device can do. And that's what I want our devices and device innovation to stand for.

The ability for a "phone", via Continuum, to be a desktop is indeed not something any other phone operating system can do (yet). It is this unique platform level capability combined with the Universal Windows Platform that has positioned Redmond's mobile strategy on a divergent "evolutionary" path from rivals Apple and Google. A path that I contend will allow Microsoft's mobile efforts to accommodate progressively complex personal computing demands unencumbered by barriers inherent to Apple's and Google's phone-focused paradigm.

Continuum and the UWP position Windows "phone" on a divergent evolutionary path.

The current "smartphone-focused" iPhone and Android dominated mobile landscape has two major barriers preventing their transition to the next step of ultra-mobile personal computing.

Get the Windows Central Newsletter

All the latest news, reviews, and guides for Windows and Xbox diehards.

First, the current smartphone paradigm evolved from a perspective of bringing greater functionality to a handheld, app-focused slate form factor environment, as a distinct and deliberate departure from the desktop environment. Thus, a development, user interface and user experience "chasm" between the PC and smartphone evolved with the evolution of the mobile landscape. So the entire infrastructure that supports the current smartphone paradigm has built into its foundation and "DNA" that it is not meant to serve the complex range of personal computing provided by a desktop computing environment.

For the past nine years, however, the smartphone industry has struggled to reconcile the increasing demands of users and app developers for more PC-like functionality with the inherent limitations of the infrastructure of the current smartphone. Consider this: as users demanded more desktop-type power and functionality from their smartphones, the industry responded with bigger, faster and higher specced devices while maintaining the systemic barriers between "phone" and "desktop" systems.

A focus on improving "phone" hardware and updating the OS would inevitably lead to a dead end.

Though this approach has provided a limited approximation of desktop power and capabilities on our phones, the current system is self-limiting. This surface-level "throw-them-a-bone" solution did not address platform level limitations that could not be addressed by bigger, faster and shinier phones with better cameras. Thus, a reasonable analysis of the current system leads to a sobering conclusion.

First, it is virtually inevitable that user's and developer's demand for more complex mobile personal computing will continue to approach that which is usually reserved to the desktop. Thus, the focus on improving "phone" hardware and updating the OS without intentionally crossing the chasm between the desktop and "phone" environments, on a development and user experience level, would inevitably lead to a dead end. That is a plateauing of the smartphone landscape where high-end devices based on the current nature of their platforms have virtually no further to go in answering the demand for more desktop-like personal computing. And that's exactly what has happened.

Today's "mini-tablets", our smartphones, have reached their comfortable size limits and the spec race offers little differentiation between competing devices.

The spec race offers little differentiation between competing devices.

This reality is the core of the second and more profound barrier. There still exists many personal computing activities that, despite slumping PC sales, are best managed in a desktop environment that these "mini slate PCs" cannot serve. The 270 million and growing installs of Windows 10 (which is a contributor to lower PC sales), the increasing market of 2-in-1's, the 1.5 billion install base of Windows PCs, the slight increase in sales of Macs and growing niche popularity of Chromebooks are a testimony to this.

Evolving alongside this foundation, however, personal computing continues its trek toward an increasingly mobile experience. Often, a user's digital experiences are managed in the cloud, and all-in-one portable hardware is expected to be capable of managing more of the tasks currently served in a desktop environment.

That said, I believe that the company that is successful in embracing and intentionally positioning their mobile devices as "personal computers" linguistically, in relation to hardware flexibility and in broad universal platform support, will be best able to meet users' and developers' diverse mobile personal computing expectations. If this analysis is accurate a deliberate disassembling of the barriers between the mobile phone and desktop environments that evolved with the smartphone industry would, therefore, be in order.

Tearing down barriers

Microsoft's bold Universal Windows Platform and Continuum are an audacious upheaval of a mobile paradigm that has sought to bring an increasing range of personal computing experiences from the PC to the phone through hardware improvements and OS updates. Microsoft's solution is a comprehensive restructuring of the mobile paradigm which accommodates both the current state of mobile and its future, where the mobile platform is tasked with more of the weight of the desktop environment.

In fact, Microsoft's approach to mobile personal computing facilitates a strategically progressing merger of the desktop and mobile environments. The current practice of transitioning to an entirely different device (phone to a PC for example) to access a different user interface or operating system will likely ultimately be replaced, for most tasks, with a single device that adapts to a user's needs. Context conforming hardware and software as demonstrated by the Surface, Continuum and Continuum for Phone will be the bridge between a user and a particular personal computing task.

In hindsight, some might argue that had industry leaders foreseen how central the smartphone would become to personal computing a course toward unified platforms would have been an early goal of the mobile revolution. That may or may not be true. Apple's Tim Cook has publicly stated OS X and iOS will remain distinct platforms.

"We feel strongly that customers are not really looking for a converged Mac and iPad …what we're worried would happen, is that neither experience would be as good as the customer wants."

Of course, Apple is a notoriously secretive company. And they have set a precedent of denying a particular strategy virtually up until the time they launch a new product or initiative that contradicts that public profession. Larger iPhones, for example, (though leaked) were denied as a course the company would follow due to ergonomic "common sense" benefits of smaller devices.

That said Apple is publicly pursuing building a closer relationship between iOS and OSX via Continuity. Though, given their history, a merger of the platforms can't be ruled out entirely.

Furthermore, Google is pursuing bringing Android and Chrome closer together as well. The company's SVP of Android, Chrome OS and Chromecast, Hiroshi Lockheimer, is on record, however, stating that a total merger of the platforms is not on Mountain View's roadmap.

"While we've been working on ways to bring together the best of both operating systems, there's no plan to phase out Chrome OS."

The 2016 introduction and 2017 release of the composite Android/Chrome OS, combined with the practical applications of Apple's Continuity, puts Microsoft's Universal Windows and Continuum strategy under tremendous pressure for success.

That said those plans committed to by Microsoft's rivals are wrought with challenges that prevent them from providing as comprehensive a solution of bringing desktop level personal computing to a mobile form factor as Redmond's strategy provides. We will delve deeper into each of these strategies in part three of this series. But suffice it to say, though I contend Microsoft's strategy offers the best solution, Apple's and Google's combined 97% mobile share positions their solutions as a "default" to the vast majority of mobile users.

Thus, the success of Microsoft's Universal Windows Platform rests in the weight of the firm's success in the PC space and its 1.5 billion install base. But not likely in the way many may think.

Bridging the PC gap with PC apps

In, Windows Phone isn't dead part VI, we took a deep dive into Microsoft's efforts to build an app ecosystem. This area, of course, is the Achilles heel of Redmond's mobile strategy. It is so profound a problem that even non-techies are known for stating, "Windows Phone has no apps." There is no shortage of apps, or programs, however, in Microsoft's desktop PC environment. As a matter of fact, during Microsoft's Build 2016 Developers Conference Microsoft boasted that there are sixteen million legacy Win32 apps currently available on Windows. That's a lot of apps.

The PC is not dying, but it is changing.

Microsoft is aware that despite declining PC sales due to the increase in mobile personal computing, the PC is not dying — it is changing. This reality is combined with the fact that many personal computing tasks are still optimally facilitated in a desktop space. Personal computing then is both a mobile and static experience. One where tech firms are working to build systems (i.e., Apple's Continuity and Microsoft's UWP with Continuum) that will help users move seamlessly between these environments.

Microsoft realizes that the 16 million legacy Windows apps will always have value. I believe that the company sees them as powerful tools that simply need to be updated, or evolved, to adapt to the new world of mobile and desktop computing. This juncture is where Microsoft's Project Centennial Bridge, which was strategically pushed during Build comes in. In a nutshell, this Bridge can be used by developers to convert their Win32 desktop app to a Universal Windows app that works across form factors.

The arguments regarding parity between certain Win32 apps and their Universal Windows app counterparts can be debated in comments, the forums or social media. Here, I am simply addressing the goal of the initiative. Which is to bring legacy apps to the Windows 10 Universal Platform.

This topic is usually discussed, argued or debated within the context of how this Bridge will bring apps to Windows "phone." The argument that is often made is that no one wants desktop apps on a phone. Fair enough. But let's look at this from another angle.

I see your 1.5 million apps and raise you 1.6 million

First, let's consider the broad picture. Microsoft's ultimate goal is to bring legacy (and other) apps to the Universal Window Platform. This platform incorporates many form factors including the desktop PC environment that, as we discussed, still has a place in personal computing. Legacy apps converted through the Centennial Bridge or desktop app convertor can be coded as universal apps that will work on all form factors and will also be distributed through the Windows Store.

If just 10% of these 16 million apps are converted to Universal Windows apps 1.6 million new apps will have been added to the Window Store. When added to the nearly half million apps already in the Store that would bring the total number of apps to approximately 2 million.

Of course, Apple's and Google's app stores, which currently both boast about 1.5 million apps apiece, will continue their upward trek as the Windows Store is populated with "bridged" apps (if successful). But via Centennial alone, 10% of the available Win32 apps would effectively (numerically) close the app gap.

The Centennial Bridge updates the familiar desktop with apps adapted to a static and mobile environment.

Both the practical availability of these apps via the Windows Store and the symbolic victory the successful execution of this strategy brings would be of great benefit to the platform. Other developers, who have neglected Windows may be encouraged to invest time polishing or building apps for the platform after seeing the potential vitality such an app surge would bring the ecosystem.

If nothing more, this Centennial Bridge strategy succeeds in updating the familiar desktop environment so that programs that we are accustomed to are adapted to a world with both static and mobile computing demands. That takes care of the software. The hardware is the next piece to this puzzle.

You say phone, I say ultra-mobile PC

The question has been asked, "Who want's desktop apps on a phone?" The answer to this rhetorical question is an implied, "no one." The question that I ask is "who wants desktop apps on a PC? The implied response of course is, everyone. I believe, as I posited last year in "Will Microsoft's rumored Surface Phone be a re-imagined Surface Mini?, and in part one of this series that the anticipated Surface Phone will not be a "phone" at all.

Will the Surface Phone be a re-imagined Surface Mini? https://t.co/5wzrjFG9hk @thurrott @leolaporte @maryjofoleyWill the Surface Phone be a re-imagined Surface Mini? https://t.co/5wzrjFG9hk @thurrott @leolaporte @maryjofoley— Jason L Ward (@JLTechWord) March 9, 2016March 9, 2016

I believe what Microsoft is planning to introduce next year will be an ultra-mobile personal computer. I think it will occupy the lowest tier of the Surface family hierarchy. Beneath the Surface Book which doubles as a digital clipboard and the Surface which is both a tablet and laptop, the new Surface will be a pen-focused digital notepad as well as an ultra-mobile personal computer.

Through Continuum, the UWP and Universal Windows apps, this device will allow a user to connect to peripherals to provide a desktop environment. A new feature introduced at BUILD 2016 will even allow this Continuum enabled device to project the phone UI wirelessly to any Windows 10 PC or laptop. (See time mark 6:24 in video below).

Ideally, users will have access to a host of desktop apps converted via Centennial, which will allow them to work as one would work in a desktop environment.

Though this device will be positioned as a PC, its mobility-focused hardware will allow it to accommodate the mobile aspects of Windows 10 and Universal apps. Thus, it will be capable of seamlessly conveying a user's experiences between the desktop and mobile environments.

Of course, this ultra-mobile PC will also make phone calls.

Furthermore, though making phone calls on our current "mini-tablets" ranks sixth below PC-like activity (as I shared in part one of this series) of course this potential ultra-mobile PC will also have telephony.

Wrap Up

Like all of Microsoft's first-party hardware, this new Surface will be an aspirational device for other OEMs to pattern after. And not just phone OEMs. Microsoft's PC partners may be the company's strongest allies in introducing the next phase of mobile computing as they add this device category to their product portfolios. Consider this: Since the PC market is declining due to mobile devices, ultra-mobile PCs are a natural solution. And for phones that have plateaued at a spec race-inspired dead end, ultra-mobile PCs are a natural evolution.

Ultra-mobile PCs are a natural solution to a declining PC market and natural evolution to a plateauing smartphone market.

This strategy is a long play. It involves teaching a 1.5 billion PC install base, bloggers, analysts, developers and the industry at large to rethink what a personal computer can be. This shift will take time, marketing and thorough communication from Microsoft and its partners. That said how OEMs package these ultra-mobile PCs is also critical to how they will be perceived.

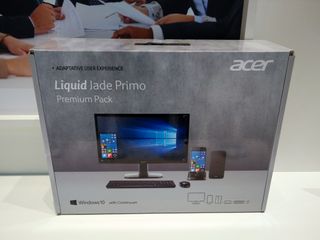

Take the image of the Acer Jade Primo below for instance. I don't know about you, but packaged in a box with an accompanying monitor, keyboard and mouse makes me think PC not phone. This form of communication is a good start.

Microsoft has come under a lot of fire for its phone strategy. How history will ultimately categorize their efforts, I don't know. But if my analysis is correct the company has been positioning its mobile strategy to play to its strength. And if there's one thing that we do know, Microsoft knows personal computers.

Jason L Ward is a columnist at Windows Central. He provides unique big picture analysis of the complex world of Microsoft. Jason takes the small clues and gives you an insightful big picture perspective through storytelling that you won't find *anywhere* else. Seriously, this dude thinks outside the box. Follow him on Twitter at @JLTechWord. He's doing the "write" thing!